- Home

- >

- Fundamental Analysis

- >

- Quantitative easing and the Japan’s case

Quantitative easing and the Japan's case

Generally speaking, QE is printing money from the central bank. The central bank then uses that money to buy state or corporate bonds. The purpose of this occupation is most often an increase in inflation or is used as a tool to help the economy during a recession. How does this happen?

When the bank tries to stimulate inflation:

Inflation is reducing the purchasing power of the currency. In general, the bank is targeting neutral inflation, typically in the range of 2-3% for developed economies. Neutral inflation neither significantly supports the economy nor hinders the economy . This is generally the best state for the bank and the economy. If inflation is below these levels, the strength of the currency becomes tangible and too expensive, which in turn leads to a reduction in the export of the country, which aggravates the trade balance. QE aims to increase the cash turnover in the country, which is generally understood as a devaluation of the currency. Large amount of money = weakening of the value of the currency.

Another important feature of QE is that it is often used during a recession and economic downturn. By purchasing state or corporate bonds, the central bank makes a financial injection of the economy. If it buys government bonds, monetary policy supports fiscal policy - the state has capital to operate - infrastructure changes, building hospitals, schools, and so on. This, in turn, creates employment and helps for a faster recovery of the economy. If the central bank buys corporate bonds, it directly gives money to the businesses themselves. This QE mechanism is considered to be quite successful, especially if the companies whose bonds are bought are in the manufacturing sector. Fusing new capital, stimulating production and allowing companies to operate normally.

What is the case with Japan?

Between the 1950s and 1980s, Japan's economy grew faster than any other G7 economy. But the astonishing success of the economy has sown the seeds of the problems. Very high real growth rates over four decades were included in asset prices, especially in stock prices and commercial property. By the end of the 1980s, asset prices had risen to even higher levels when the Japanese Central Bank tracked a very easy monetary policy, trying to prevent the Japanese yen from appreciating too much against the US dollar. However, when interest rates grew in 1989-1990 and the economy slowed down, investors finally came to the belief that growth assumptions that were pledged in asset prices and other aspects of the Japanese economy were unrealistic. This realization has led to a fall in Japanese asset prices. For example, the Nikkei 225 stock market index reached 38,915 in 1989; by the end of March 2003 the index decreased by 80% to 7,972. The collapse in asset prices has led to a drastic reduction in wealth. Consumer confidence, of course, declined sharply, and consumption growth slowed. Corporate spending has also fallen, and bank lending has sharply contracted with the weak economic climate. Although many of these phenomena are evident in all recessions, the situation worsens when deflation occurs. Deflation also raises the real value of the liabilities.

Faced with such a downturn, the conventional monetary policy response is to reduce interest rates in order to stimulate real economic activity. The Japanese central bank cut interest rates from 8% in 1990 to 1% in 1996. Until February 2001 the Japanese interest rate was reduced to zero. Once this point has been reached, the central bank can not lower interest rates as nominal interest rates can not be negative. The Japanese central bank kept its levels from zero since February 2001.

Once the interest rate reaches zero, there are two broad-based approaches. First, the central bank may try to convince the markets that interest rates will remain low for a long time, even after the economy and inflation are rising. Secondly, the central bank may try to increase money supply by purchasing private sector assets, Quantitative easing. The Bank of Japan did both in 2001. It launched a program of quantitative easing, complemented by an explicit promise not to raise short-term interest rates, while deflation did not yield to inflation.

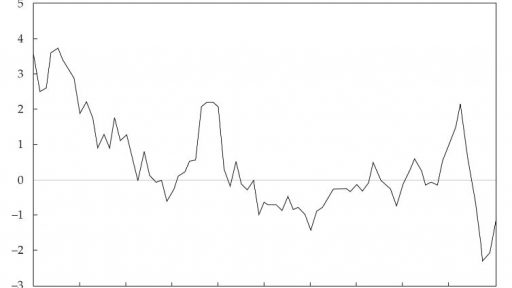

The success of this policy is difficult to assess. As the graph below shows, although deflation has become inflation for some time, it has returned to deflation in 2008-2009, when the Japanese economy suffered a sharp recession along with much of the rest of the world. At that time, after having changed its QE policy over the 2004-2008 period,

Read more:

If you think, we can improve that section,

please comment. Your oppinion is imortant for us.